An Associativity Engine

The way the human brain actually learns is fascinating. Many of use try to use the analogy of the brain as a computer, but that is not really the case. The brain much, much more interesting than that!

Why Search Can't Help

Once upon a time, (5 years ago!) I made a rather cool document designed to assess a potential customers need for a product or service. I liked it because it was the kind of sales tool that delivered value whether the person used our services or not. In short, the customer wanted to know their score. It was a powerful assessment. We used it for a while then stopped. A few months ago, I wanted to find that document and I searched everywhere on our google drive for the "Customer Assessment." I could not find it. I knew it was there, but I couldn't track it down. Every combination of search term failed to surface the source document.

Eventually, I took a different approach, I looked for the last client to use the assessment - and that's when I found it. It wasn't called an assessment. I had called it a scorecard. But I wondered, why on earth had not remembered that? Why was I looking for the wrong thing?

Because... my working, most accessible meaning for the word scorecard had changed. Four years ago, our company implemented the Entrepreneurial Operating System, and scorecards are a very important part of that system. In short, my brain "updated" my understanding, definition, and visualization of the word "scorecard." As a result, my memory of the old document shifted to the more "accurate" term "assessment." It was like my memory said, "well, a scorecard is now this, what is that thing? it must be an assessment." And that word became the "new" way I thought about something from my past.

The human brain is constantly updating its memory. As they say, memory is an act of reconstruction, not an act of recall.

Why It Matters:

Mental models are extremely powerful for shaping not only our understanding of the world, but our ability to predict what is going to happen. The human capacity to think about the future might be one of our singular gifts in the whole universe. However, every model has limitations, edge cases where it does not work. And sometimes, those "edges" are entire areas. Take physics. Newton's Laws of motion are fantastic at the macro scale, but they fall apart when it comes to Quantum Mechanics. So it goes with using the "brain is a computer" model. Useful in some cases, but very limited in others.

This is extremely important because the way our brain stores and retrieves information is radically different than the way computers do the same work. Having a better model, can help you choose a better way to help you find what you need to know, when you need to know it.

Big Picture:

The brain evolved to solve what is called the Plasticity, Stability Dilemma. How can we learn new things, without forgetting old things? How can a human brain self-organize in such a way that it can update some of its knowledge without losing all of its knowledge. If you have ever accidentally overwritten an old computer file, you have experienced catastrophic forgetting. For the most part, the brain doesn't do this.

However, there is one very specific instance that the brain does consistently overwrite old memories - muscle movement. As our body continually evolves while we grow, keeping detailed memories of every movement we ever made is not only impractical, but evolution also decided it has no value. We literally don't do it. This is one reason athletes constantly practice. They constantly have to drill in the memories over and over again. It would be like the only way you could learn you ABC's would be relearn them daily for the rest of your life.

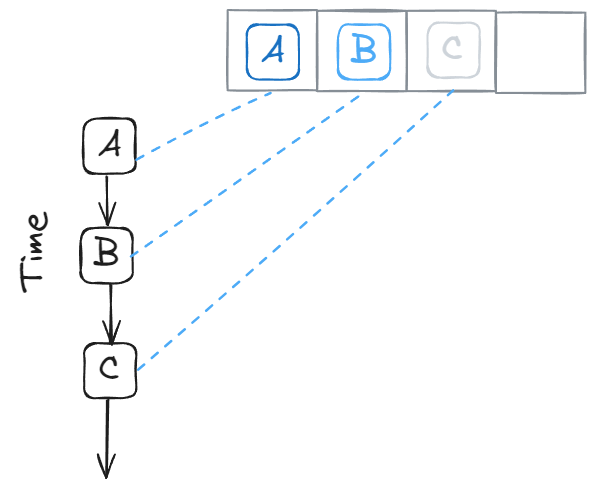

Speaking of ABC's, let's imagine you are learning them for the first time, or a new language. The computer model says you get a letter, and you put it in memory. You can think of this like putting letter tiles in boxes. One letter per box. Save the letter and we're done.

However, we know our brains don't operate like that. We need repetition. Lots, and lots of repetition.

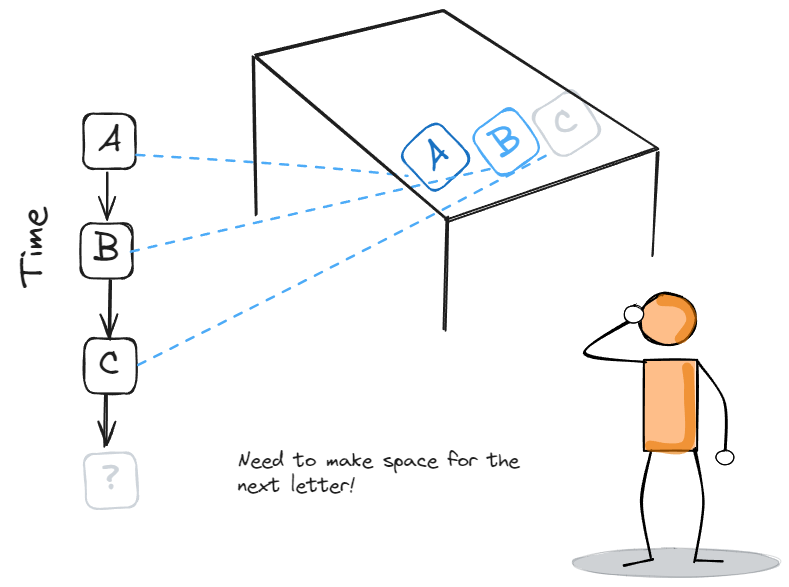

Why? First of all, when we learn a list, we don't just save letters like tiles in a keepsake box, it is more like setting tiles on a table... as more tiles come in, your brain will "push" or "adjust" the other tiles we've already put on the table...

What we learn in the future, can alter what we have already learned. But even this does not fully capture how we learn, and why we need repetition...

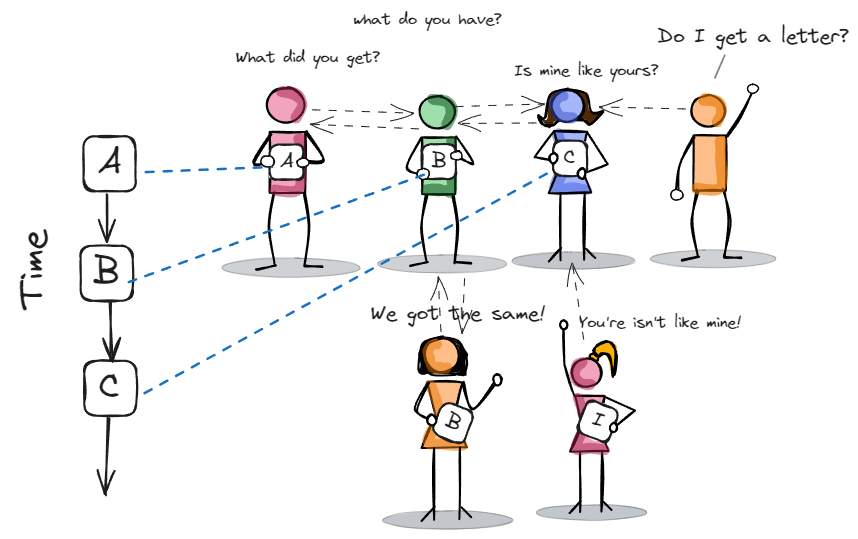

We are not putting letters on the table, imagine each letter is being handed to a person to hold, and that person is not only holding a letter, but they are also talking to the people next to them holding letters. But wait! It gets better, each person holding a letter is also talking to the people who came before them who held letters who are asking, "what letter are you holding?" Is that letter like my letter?

My point here is that there are lots of interactions for each item we learn. Why? Because we store information in neural networks, not nice tidy little boxes. Our neurons, like little kids at school, are always talking to each other, comparing, weighing, anticipating, and deciding what to do. We need repetition, because the first row of "people" to get a letter are your short term memory. The bottom row is your long term memory. We use a complementary competitive set of neural networks to decide what moves from short term, to long term memory, and repetition, along with association is how new information sticks in our head. This is how we solve the "stability-plasticity" dilema. Storing information is not as simple as putting data in a box, it is a process, one that is largely driven by associations and connections to already existing information.

So What!?

This interaction of iteratively updating information in our long-term memory in part explains why my "memory" of the scorecard changed to a memory of an assessment. It wasn't just the word "scorecard"; it was the association of all the features (called qualia) around that concept of the document that get stored and updated.

Notice how I eventually ended up finding my document. By searching for something related.

And that brings me to why I started spending so much time building a Personal Knowledge Management system. I wanted a tool, that worked the way my brain worked, that helped me weave new knowledge into my existing memories. I wanted a tool that would grow more resilient, not fragile over time. In short, it needed to evolve with me.

Takeaway:

One of the reasons connected note apps have become so popular is that they can mimic the associative nature of how our human memory works. It has happened to me that how I label that past can evolve over time, making it difficult to search for old work, but having more associations can make it easier to recall that information.